RealLife Steampunk: A Martini-Henry Grenade Launcher

There’s an article title I never thought I’d write! A Victorian grenade launcher? Not quite. It is indeed a Martini-Henry grenade launcher, or to be precise, a Blanch-Chevallier Grenade Discharger. Rather than being designed to combat Zulus on the South African plains, it was actually conceived later, at a time when both sides in the First World War were becoming bogged down in trench warfare. The same imperative that drove the invention of overhead fire rifles, mortars, medieval-style melee weapons, revolver bayonets, and yes, rifle grenades, also gave rise to this (so far as we know) unique prototype. It’s a crazy combination of forward thinking and retro technology; almost the definition of ‘Steampunk’!

VIDEO

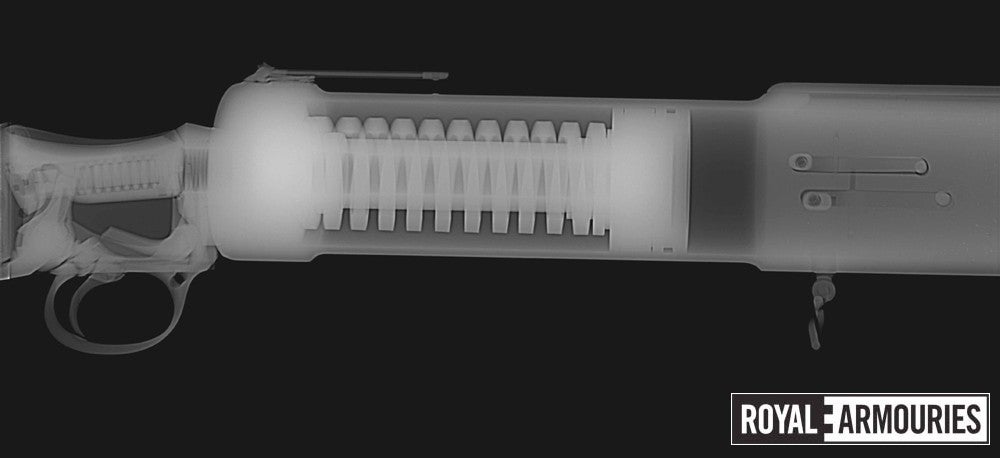

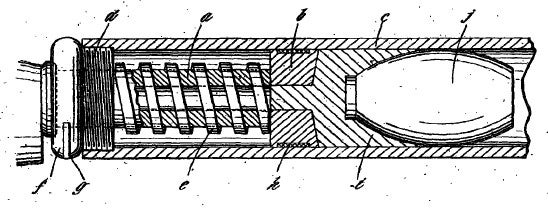

I have to confess that when I first re-discovered this piece in a back room at the UK National Firearms Centre, I suspected that it was the firearms equivalent of a stuffed Jackalope or mermaid; different species stitched together to create an amazing and bemusing hybrid creature. After all, it had come to us from a movie prop house and could easily have been ‘bodged’ together in recent decades. But, just as it turned out that the platypus was a real animal, so this piece is a genuine, if experimental, weapon. We X-Rayed our gun, and as you can see, it’s a close match to the original patent drawing further down.

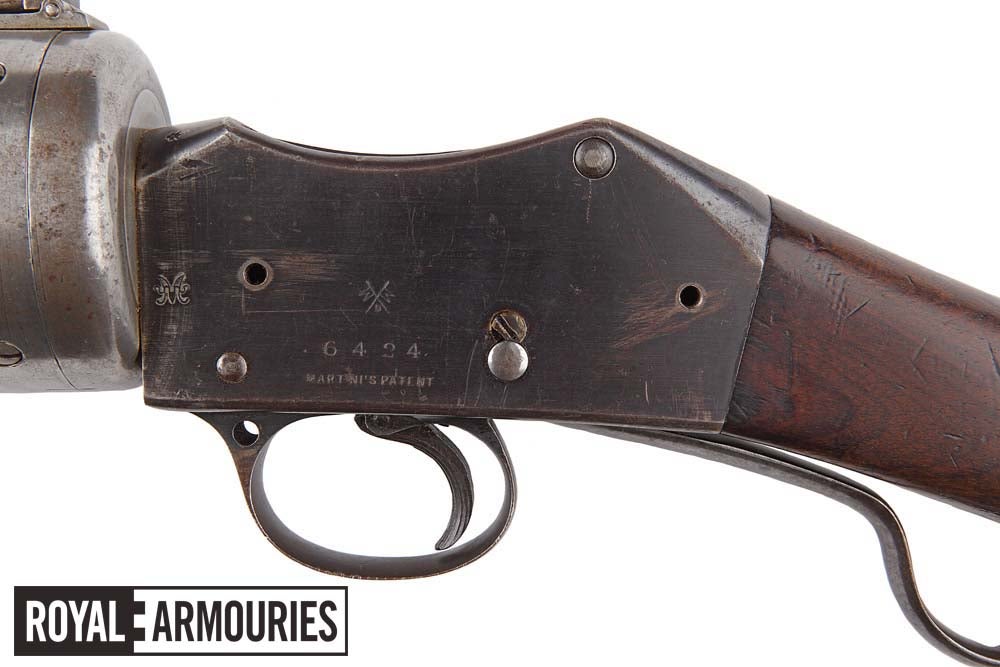

Despite being described in its only published reference as (Brown, 2004) as a ‘Muzzle attached grenade discharger’, this improbable-looking beast is actually a complete weapon, not a mere accessory. It’s built on an 1880s-vintage commercial Braendlin Armoury Company stocked action in the original .450 Martini (.450/577) calibre. The marks on the left hand side of the receiver are the crossed pennants and ‘B’ of the company, and the script ‘M’ of patent-holder Friedrich Von Martini. Replacing the usual rifle barrel assembly is an enormous, heavy barrel of 2.5” bore, equipped with a sprung piston platform. Unlike the PIAT launcher of the Second World War, this big spring does not actually launch the projectile. The grenade would actually be fired by a .450 blank cartridge, the spring serving to dampen the (significant!) resulting recoil. Whereas the rifle grenades designed for the SMLE rifle were to be fired braced into the ground, this spring, the thick rubber buttplate, and the tall tangent backsight are all there to permit firing from the shoulder. This is an M79, circa 1916!

The relevant British patent can be found online, and details the method of operation. The grenade illustrated is not the standard British Mk.36 ‘Mills bomb’, as it is the wrong shape and physically too wide to fit the launch tube. This gun would have fired a proprietary round around the same weight as the Mills bomb, but with a ‘tapered base’ and, presumably, a locating rib along the top to engage in the channel cut into the bore of the launcher.

The tube is also equipped with two sprung pivoting levers to retain the grenade when the weapon is carried loaded. This is a worrying prospect, as the Martini action lacks an applied safety, meaning the the gun cannot be carried loaded with both grenade and propellant cartridge without risk of accidental discharge. Had the design been developed further, no doubt this would have been addressed. Intriguing reference is made in the patent document to the possibility of firing canister shot from this weapon!

The ‘Blanch’ in ‘Blanch-Chevallier’ is Herbert John Blanch of the London gunmaking firm of J. Blanch & Son. Blanch had published a standard work on sporting guns, entitled ‘A Century of Guns’, in 1909, and had been chair of the Gunmaker’s Association. As Blanch was part of a long line of skilled gunmakers, but Chevallier is listed in the patent as a ‘firearms technician’ and was the more prolific patent holder, it seems likely that this prototype was built by the Blanch but designed largely by Chevallier.

Arnold Louis Chevallier was born in 1868 in Switzerland, but by 1911 was listed in the British census as a mechanical engineer and expert in small arms and explosives. He lodged a range of other patentsincluding a followup to his grenade launcher; a mortar on the same principle, submitted the following year. Chevallier also worked on sporting shotguns, and a series of semi-automatic rifles dating back to at least 1912 and based upon Sjogren’s inertia recoil principle. As Ian of Forgotten Weapons notes, we have the British Sjogren trials rifle from 1908 in the NFC collection. Chevallier’s design was no attempt at patent avoidance, as he co-authored an article and a book with Sjogren himself. References exist toseveral other publications of his on the subject of firearms, ammunition, and artillery technology, none of which are available online, unfortunately.

There is a bizarre twist to the story, however, when we consider the inscription on the left side of the weapon:

This is marked ‘Enever – Chevallier Patent Automatic Small Arms Company Limited’. Another contributor to the design? Probably not. Edwin Alexander Enever was also an immigrant to Britain, from another part of the Empire, having been born in India in 1872. He came to Britain around the same time (c1910) as Chevallier, and began an extraordinary career as an engineer and financier. His life is detailed on a genealogy website, but here’s the short version. Enever first came to the attention of the authorities for a minor offence in 1913, and filed for his first bankruptcy in February 1914 (this doesn’t appear on the afore-linked site). It was at this point that he founded the above firearms company with Chevallier, presumably seeing weapons as a fruitful opportunity given the storm clouds gathering over Europe. He was accused and acquitted of several investment frauds during and after the war years, and filed for bankruptcy again in 1922. Eventually, the following year, he was found guilty along with two others of another charge of fraud relating to investment opportunities in the Chinese mining industry. For this he was convicted and sentenced to prison for three years, leading to a description in acontemporary newspaper report as:

“…a monocled rogue…who juggled with money as easily as does the flirt with the hearts of men”.

Which makes it sound like he liked to tie women to train tracks and creep away whilst twirling his moustache: in cash-strapped post-war Britain, his crimes were probably regarded as about as bad. He also seems to have avoided serving his country during the war itself, and if there’s one thing people dislike more than a con-man, it’s a draft-dodger! He even combined the two offences by involving military officers in his scams, stranding them overseas without the money to get back.

There’s nothing to suggest that Chevallier was himself defrauded by Enever, but the partnership was clearly not a fruitful one either. The two lodged just two patents together, a 1915 incarnation of Chevallier’s rifle, and a 1916 tweak to its magazine. Strangely, although the inscription on our grenade launcher references Enever, the actual patent does not. Perhaps having had Blanch build his prototype, Chevallier was already becoming disillusioned with his business partner?

In any case, Chevallier continued work on his automatic rifle until 1947, apparently to no avail. His and Blanch’s contributions to the history of technology in general and to awesome grenade launchers in particular, were largely forgotten. I hope this article changes that, though we will never know what tactical contribution this weapon might have made to the war.